There is nothing more satisfying for a woodworker than to watch two pieces of wood become perfectly mated together as you tighten the screws, set the mortise and tenon, or slide the dovetails together. Creating the perfect joint that permanently turns two pieces of wood into a seamless, enduring creation is after all, the essence of what we do in our shops.

But perfect joinery is also the hardest thing to master. There is simply no room for the slightest error. One miniscule mistake of cutting or even sanding can turn a carefully honed piece of your final product into nothing more than scrap lumber. But fear not, my humble beginner, for you are in good company. Every woodworker on earth can point to a heap of scraps. You’re in good company.

What separates the Greats from the Rookies in the shop is more about knowledge and the right tools than it is about superhuman skills. So, let’s get you equipped with some of the Right Stuff it takes to bring your woodworking to the next level with 7 wood joinery techniques that are sure to “Up” your game.

Glue

Human beings have been using some form of glue to hold things together since a caveman in what is now Italy figured out that he could hold two rocks together with birch bark tar to create a simple axe. Humans have come a long way since that day, and so has glue.

While there are many types of glue on the market, the one best suited for wood joinery is commonly known as “carpenter’s glue” or “yellow glue” because, well, carpenters use it and it is yellow. Technically, it is known as Aliphatic Resin Emulsion. It adheres well to wood, doesn’t require a thick application, and lasts a long time.

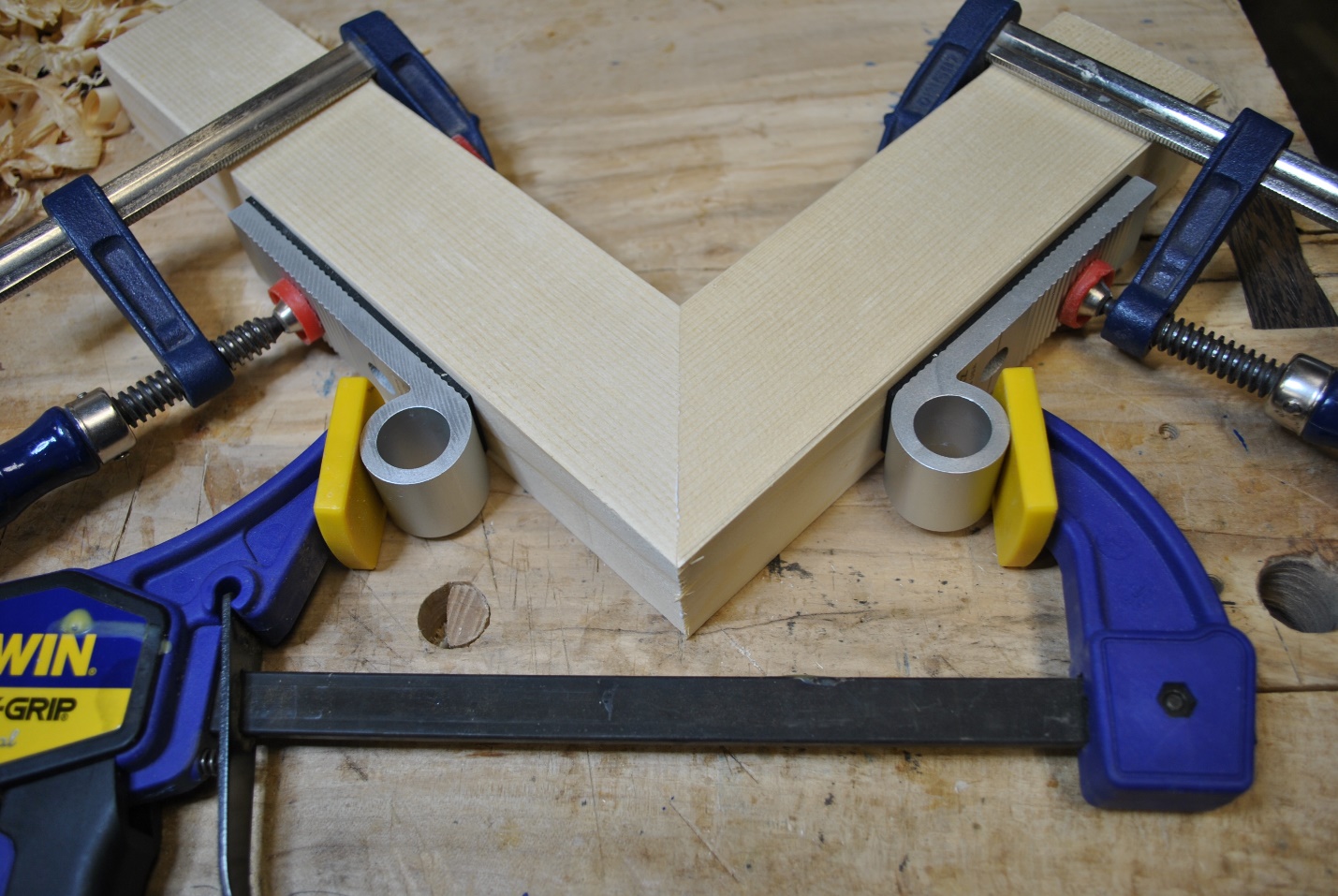

The best glue joinery involves smooth, well-matched edges. A small amount of glue is spread thinly across both joint faces and the pieces are firmly clamped together until the glue dries. Excess glue that seeps out of the joint will seal the wood grain and spoil any chance of staining the wood. There are two schools of thought on how to deal with excess glue. One is to wipe it away immediately with a damp cloth. This can work if the amount of excess glue is small. However, if you have large gobs of glue squeezing out, trying to wipe it away can result in spreading the glue over more of the surface area that you are trying to protect. A better choice may be to let the glue dry until it begins to darken in color, then trim it away with a sharp chisel.

Gluing is so fundamental that it is an essential element of every other form of joinery that we are going to discuss. You won’t get away from glue, so learn how to use it correctly.

Pocket Screws

The wonder of great joinery is that two pieces of wood seem to be held tightly together by an unseen force. In reality the force is very tangible – you just have to know where to look. Pocket screws are a great way to hide the force.

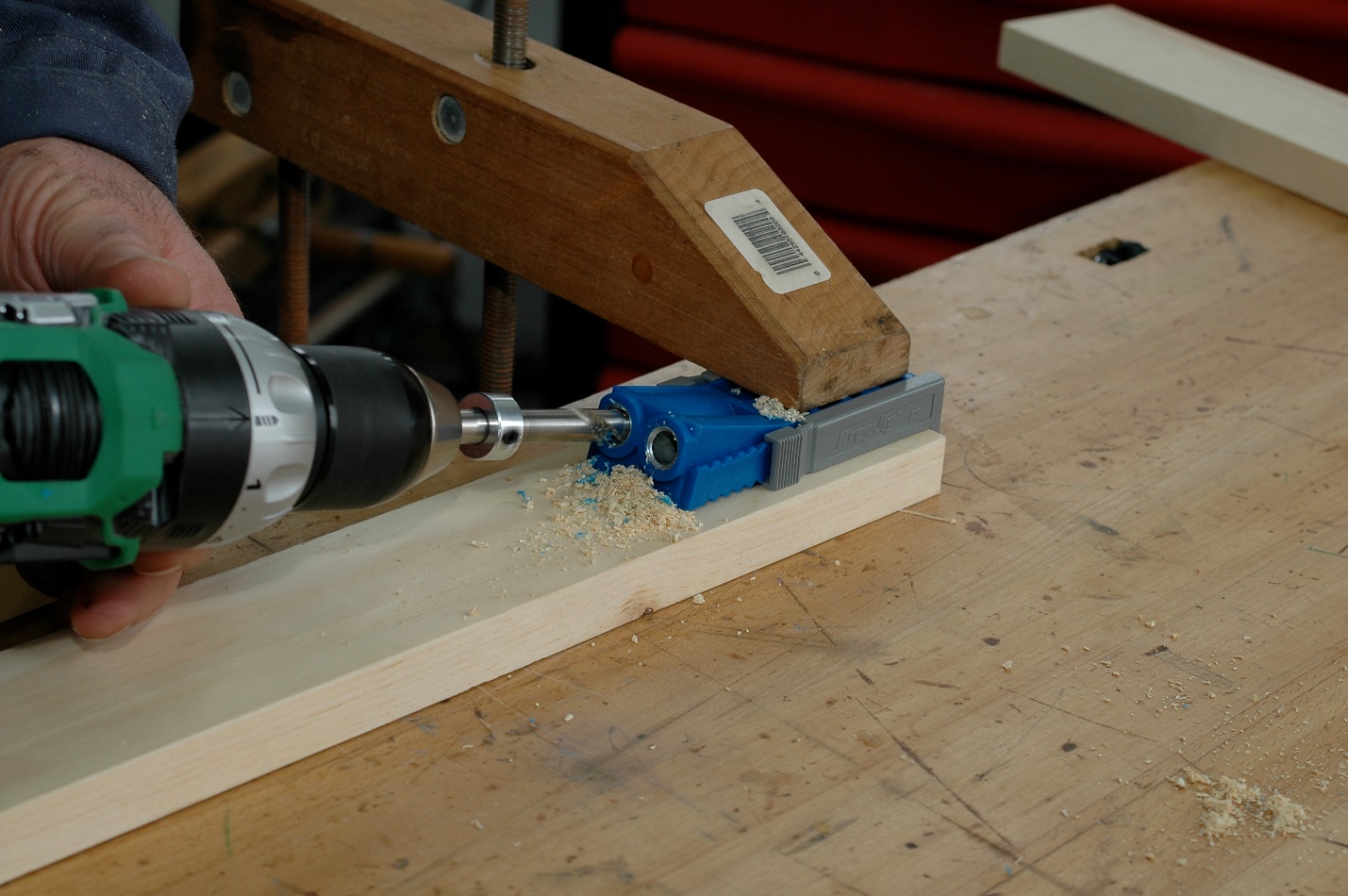

A pocket screw is inserted at a sharp angle into one side of a piece of wood so that it will project out the grain end of that piece and into the piece to which it is being joined. It’s a simple concept, but with angles and measurements that are very difficult to calculate. But fear not! We don’t need to do the math because the engineers at Kreg Tools have done it for you.

For about $45 bucks you can arm yourself with the Kreg Jig® R3 kit that will have you making perfect pocket screw joints every time. The kit comes with a jig for drilling perfect pocket holes, along with the drill to do it, a sampling of pocket screws and the special square-tipped driver to tighten them.

Just set the length of the jig’s adjustable arms to the thickness of wood you are working with and clamp it to the face of the board. Adjust the lock ring on the drill bit to the proper depth (there’s a gauge built right into the kit’s case) and run the drill bit into the rig until you reach the stop ring.

Remove the jig, apply a thin sheen of glue to the two edges being joined, insert the pocket screws into the holes and drive them tight. Wipe away the excess glue and let it dry. You can even take things a step further by gluing angle-cut dowel pieces into the pocket holes and sanding them smooth with the surface of the wood. You just created a very strong joint with invisible screws. Or, in the case of the example below, you can use the dowels to create interesting offsets.

Biscuits

No, I’m not talking about using Grannie’s day-old biscuits to gum a couple of pieces of wood together. The biscuits I’m talking about are thin, oval-shaped chips of compressed wood shavings (usually beech wood) that fit neatly into slots cut into the two edges to be joined.

When glue is applied to the biscuits, they swell up from the moisture and (along with the glue) form a very firm, strong bond between the pieces with no visible attachment from any angle. Biscuit joints are perfect for fine cabinetry work and edge-to-edge joinery where the desire is to completely hide any hint of joinery technique. A table top made of multiple pieces of wood joined side-by-side is a perfect example of where biscuits would be used.

The trick is that the slots cut into the two faces to be joined must be perfect. So perfect, in fact, that there is a special tool called a biscuit joiner (sometimes called a plate joiner) designed just for making these edge cuts.

Miter Joint

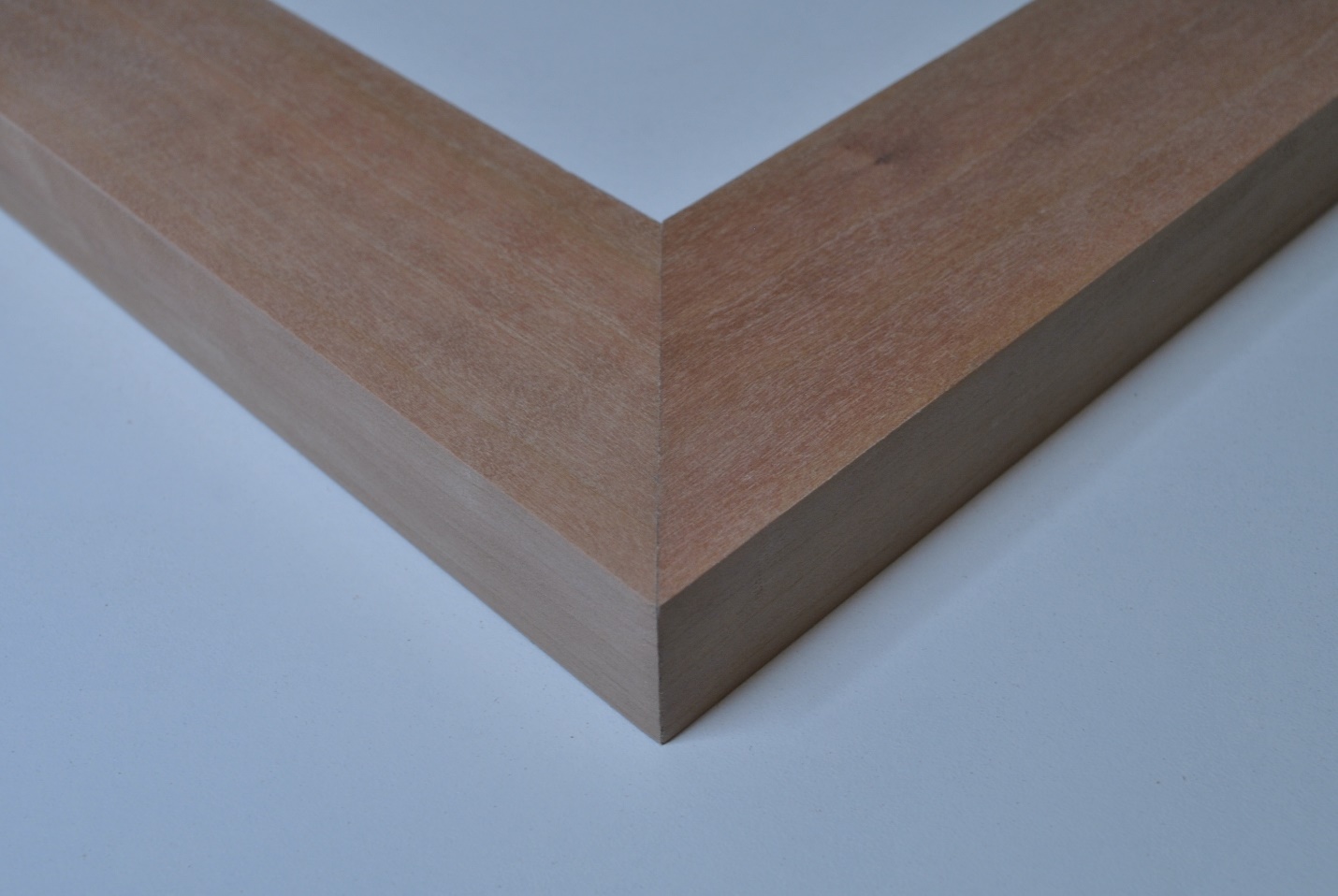

Two pieces of wood, each cut at a 45° angle form a perfect corner. Put four pieces of equal length together with four mitered corners, and you have a square. This is the fundamental shape of all woodworking (except lathe work, which is a woodworking art form all of its own).

The miter joint is a beautiful joint. It allows the grain of two pieces to create a symmetry that is very pleasing to the eye. That’s why mitered corners are often employed on trim pieces and other forward-facing elements of a design.

It is, however, not the strongest of joints. While it does provide a wider gluing surface than a straight butt joint, a miter cut usually needs some help. Biscuits or pocket screws can be employed to help strengthen a miter cut.

It is also necessary to be sure the mitered surfaces fit perfectly together. Since the mitered joint is a true design element, it means the alignment of the edges must be flawless.

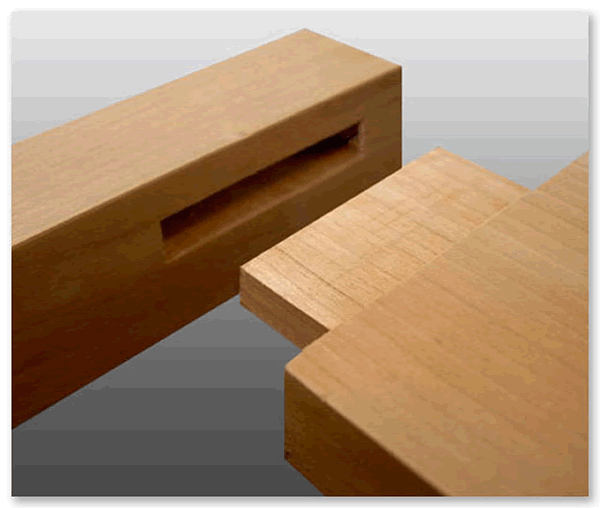

Dado Joint

A dado joint is very handy where you want to join an edge into the middle of another piece of wood, for example a bookshelf into the frame. There are two basic ways to create the dado groove. The first is by using a table saw and a blade set known as a stacked dado head cutter. This consist of 2 saw blades with “chippers” that can be placed between them, like spacers. By “stacking” more chippers between the blades, you can create a wider groove to accommodate thicker stock, and vice versa.

The other method is to use a router and straightedge or specially designed router jig to create the dado groove. Be careful as you do this because running your router at too high a speed can result in burning the wood.

Whichever method you use to cut the dado groove, remember not to cut too deeply into the stock. A general rule of thumb would be to cut a dado no deeper than one-third the thickness of the pieces you are cutting. Any more than that can lead to structural weakness. For example, if you are cutting dado grooves for shelving into a ¾” thick standard, make the cuts no deeper than ¼”.

Mortise and Tenon

There was a time when woodworkers didn’t have things like pocket screws, beechwood biscuits, miter saws, and dado head cutters. They had to figure out how to permanently join two pieces of wood together without any hardware. The mortise and tenon joinery method is one of the oldest in woodworking, but it’s every bit as good today as it ever was.

The mortise is a cavity cut into a piece of wood, and the tenon is the end of the adjoining piece that is cut down in size to fit snugly inside – with glue, of course. There are varieties of mortise and tenon joints that employ wedges and other methods of securing the joint as well. In fact, even the biscuit joint is a form of mortise and tenon, but let’s stick to the basics for now.

At that basic level, a mortise and tenon joint is really just a peg stuck in a hole. It’s how you get there, and how you turn it into a perfect joint that makes this an interesting joinery method.

The mortise can be created using a drill press, by drilling multiple holes very close together. There are even special drill bits with chisel-like attachments that create square-edged drill holes. The tenon is accomplished by sawing or milling the end of the adjoining piece to the proper dimensions.

Another method is to use a router in a specially designed jig, like the one from Trend® that makes quick work of creating perfect mortise and tenons in a variety of designs. One of my favorites creates a mortise and tenon based on a mitered corner. Class and strength all at the same time!

Dovetail

This is the pinnacle in all of joinery. The dovetail provides immeasurable strength, a large surface area for gluing, and flat-out looks cool. Nothing says “I know my way around a woodshop” like a piece built with dovetail joinery.

The tensile strength of a dovetail joint can’t be beat. It is comprised of a series of “pins” that are cut in a trapezoidal shape to mesh perfectly with an opposing set of “tails”. When these pieces are glued together they form a joint that is virtually impossible to pull apart. Dovetail joinery is most common in box-shaped items such as drawers, jewelry boxes and cabinets.

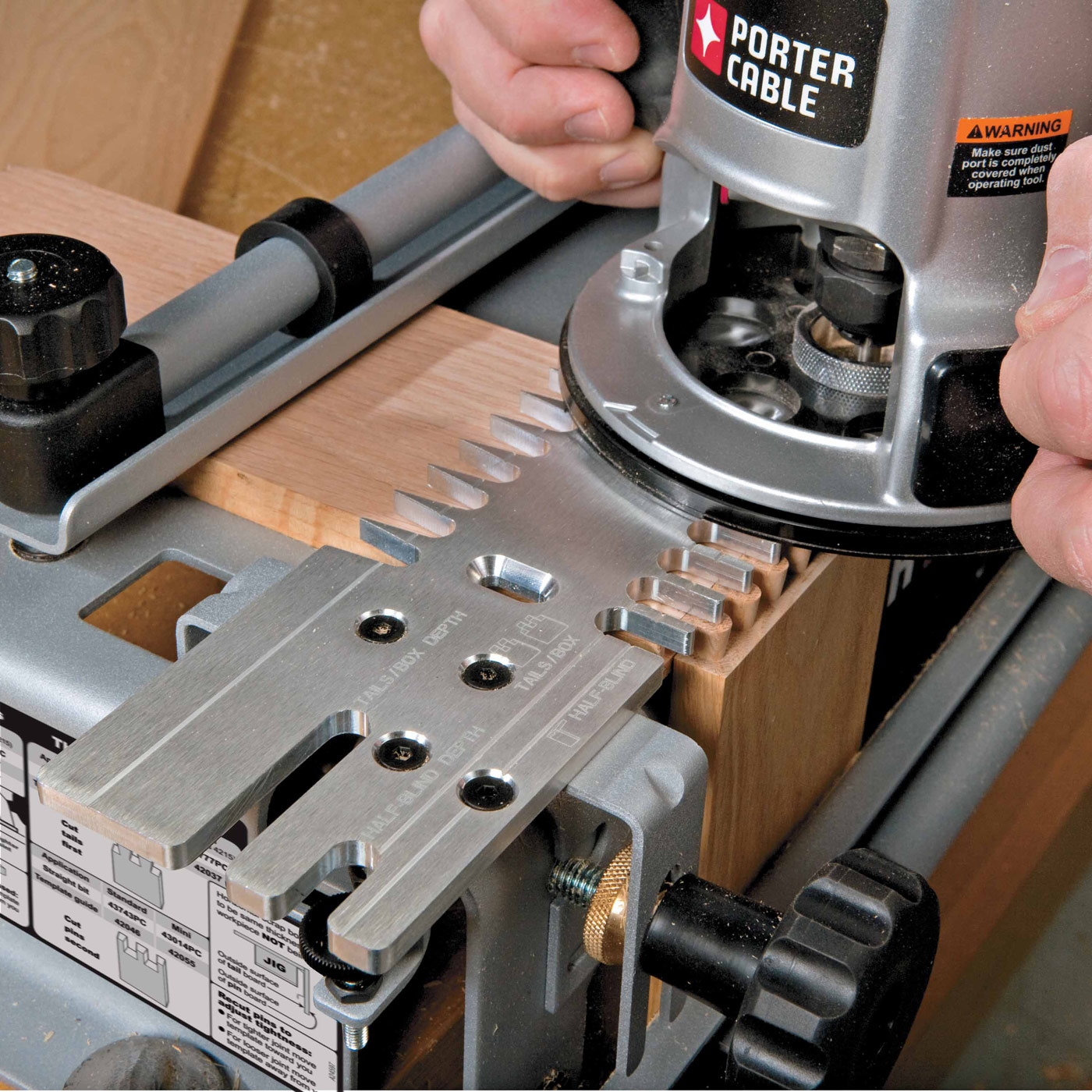

There are many ways to create dovetails. There are router jigs, saw blades, and hand-carving techniques. A review of just the jigs available would make a website all of its own. I’m not saying it’s the best, but there is a 12-inch jig for routers from Porter-Cable that is widely available at big box lumber and hardware stores.

It makes quick work of creating perfect dovetails every time. The Dovetail joint is as versatile as it is strong and should be a go-to choice for any woodworker.

Conclusion

That is my list of seven joinery techniques that every beginning woodworker should learn to master. Bear in mind that for each of these there are hundreds of design variations and they can be scaled up and down in size in many ways. But with even a basic knowledge of these joinery techniques, you can make just about anything. 3 easy woodworking project for beginners can be found here.

These joints really aren’t that hard to do as long as you stick to my sound fundamentals of wood working: Measure twice, cut once; Buy high quality lumber; Use the correct tool for the task; Don’t hurry; Practice safe procedures; Measure two more times before you make that cut.

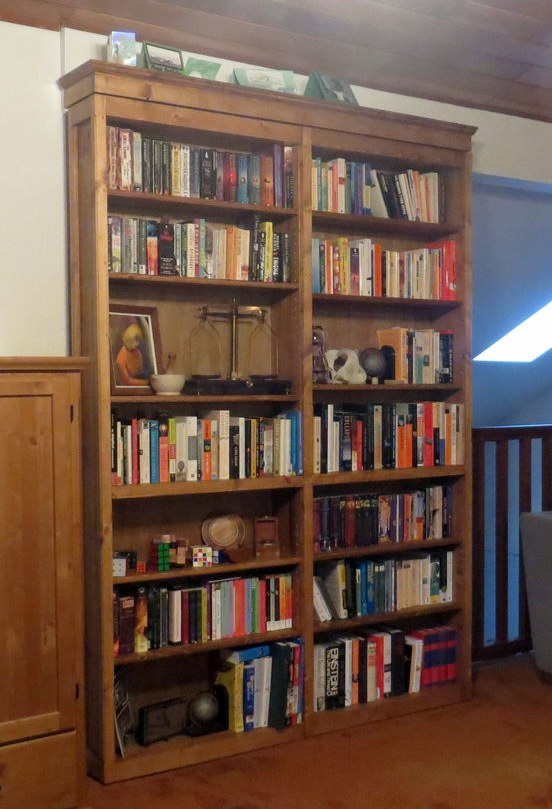

So, you want to build a bookcase. Whoop-de-doo. It’s a rectangular structure with horizontal shelves. About as exciting as watching the grass grow, right? Now, what if I told you that your bookcase could be used to hide the best secret in your entire house?

Using a bookcase to hide a secret room is certainly not new. The concept has been used in many stories, movies, and even board games. But do you anyone who really has one? Maybe you do, and you don’t even know it. Well, here’s your chance to be the first one on the block to have a secret room hidden by a bookcase…or, are you really first?

Materials

- (2) ¼” finish plywood sheets

- (6) 1”x16”x8’ Select pine boards, pine project boards, or hardwood of your choice

- (6) 1”x2”x8’ select pine or hardwood to match.

- Murphy Door Kit (More about this later)

- Pocket screws, Miller dowels, or both (whichever you prefer for assembly)

1” wood screws - Wood Glue

Tools

- Table saw

- Miter saw

- Hand Planer

- Router

- Drill

- Kreg KMA3200 Shelf Pin Drilling Rig

- Screw Driver

- Tape Measure

- Pencil

The Plan

First, you need a small space in your home that can be essentially “walled-off” by this bookcase. Perhaps there is a small alcove on the side of the family room or your bedroom that lends itself to be hidden. Depending upon the floor plan of your home, you may even be able to hide an entire large room of your basement. This bookcase is the perfect way to hide that “man-cave” you have always wanted.

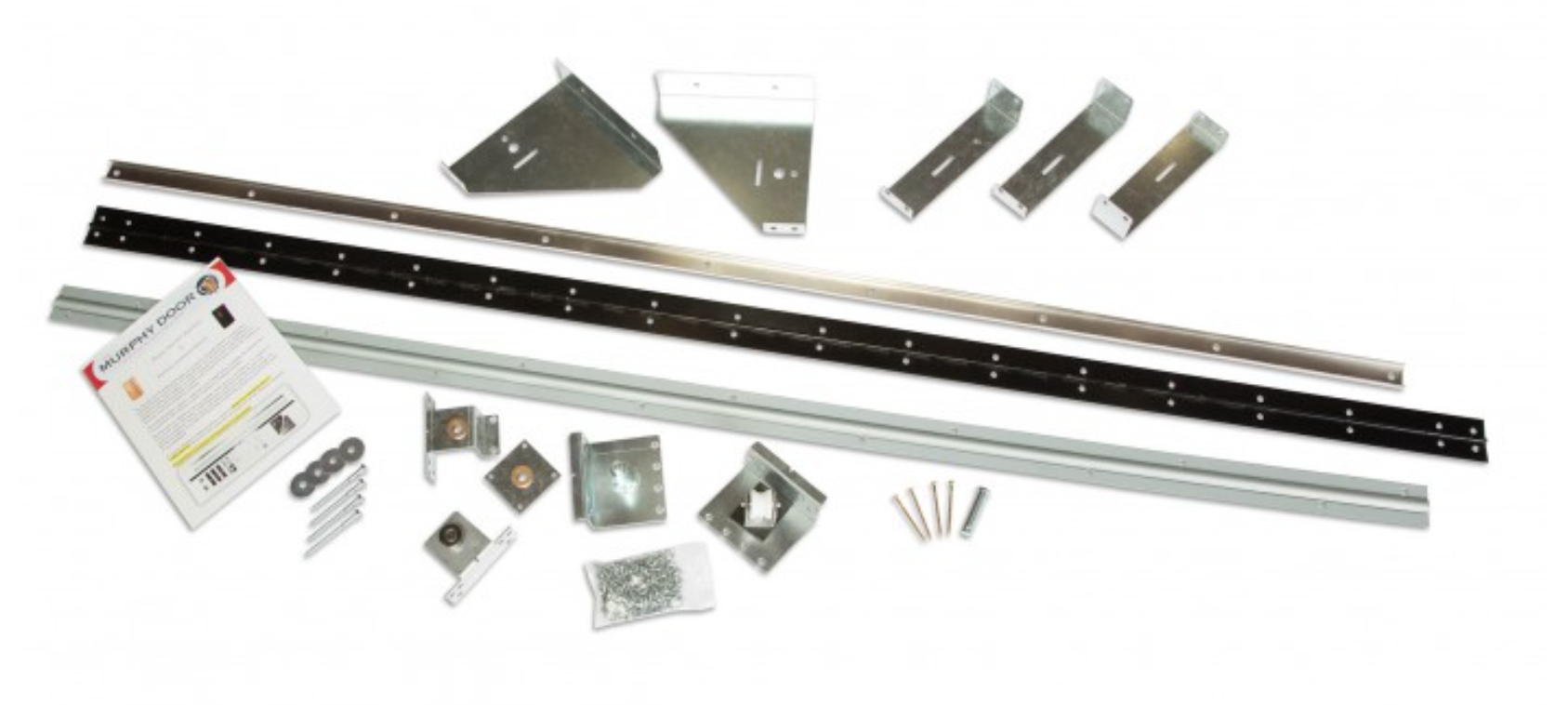

Now, about that Murphy Door Kit. The Murphy Door Company actually sells completed bookcases like we’re building, but where’s the fun in that? They also sell the hardware kit, which I think is the way to go. You can use the type of wood and create a style of bookcase that matches your home directly. The more this bookcase blends in to its natural surroundings, the more hidden your secret door will be.

The Cutting

You are essentially making two bookcases that get joined together in the middle by a full-length hinge. So, for every “left” bookcase piece, there is a mirror “right” piece.

Rip 2 boards 7 1/2” wide and 83 7/16” long. Market them “inside left” and “inside right”.

Rip 2 boards from the remaining pieces 7 ¼” wide and 83 7/16” long. These are “outside right” and “outside left”.

Rip 3 more boards to 7 ¼” widths and cut 18 pieces 28 ¼” long. Four of these will form the tops and bottoms of our shelf units. Two will serve as center shelves, which will be hard-mounted in place to add strength. The remaining 12 will be adjustable shelves, and will require trimming down by an eight of an inch or so, for easy placement inside the unit.

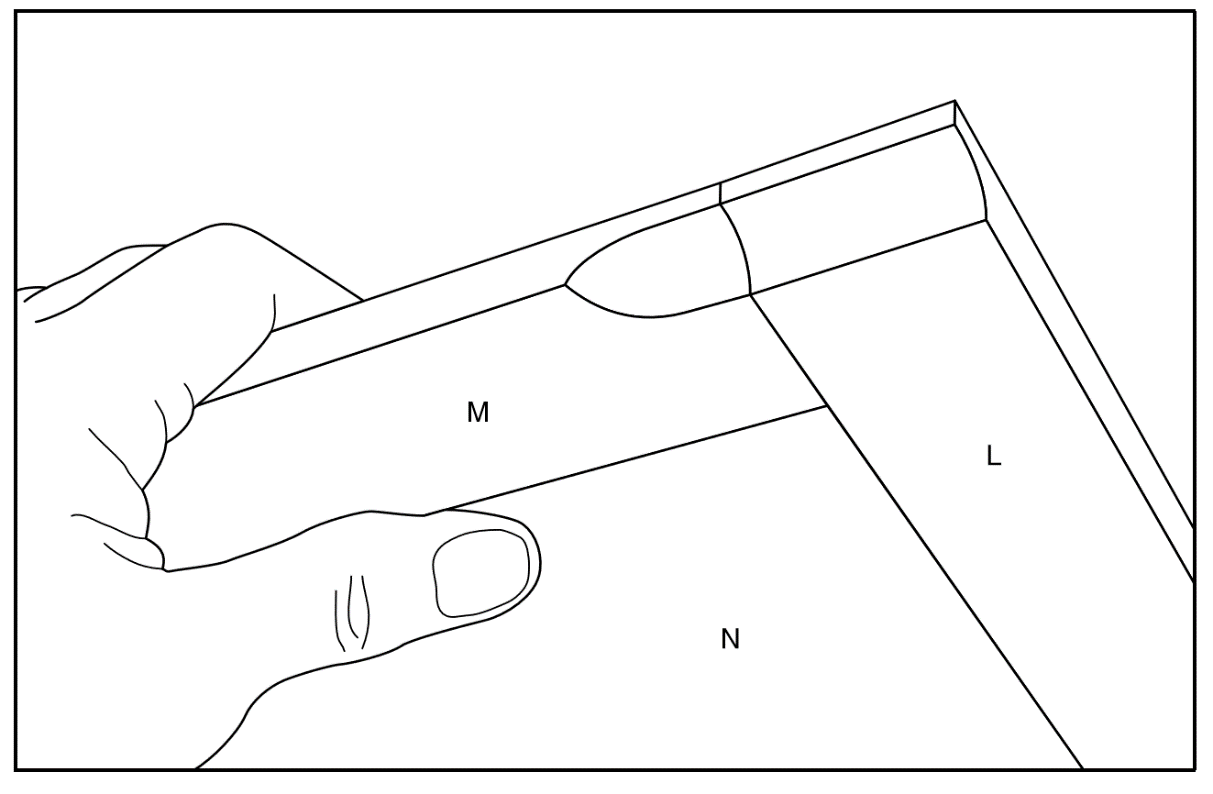

Trim the front edges of all of the shelf pieces with a router, if desired. Also, cut a rabbet on the inside back edge of all framing pieces to accommodate the plywood backing.

Cut the 1×2’s to match the lengths of the bookcase frame. These will be used to form a face trim on the framework. These trim pieces get mounted flush with the inside edges of the box created by the framework. Only one of the inside edges gets the trim – that way it covers the seam between the two sections. When the bookcase is closed. The top and bottom face pieces hide the slider hardware.

From the remaining piece of your lumber supply, rip a strip 7 7/8” wide and 59 ½” long and mark this “valance”. Now rip a 3 9/16” strip 59 ½” long and label it “valance back”. A piece 2 ¾” wide and 61” long gets marked “valance front”. And two pieces 2 ¾ x 8 5/8” will become “valance left” and valance right”.

Finally, cut the plywood sheets down to 83 7/16” by 29 3/8”.

The Build

The two outside pieces of the bookcase frame get the sliding door hardware attached to them, and a notch is required at the top and bottom to accommodate this. Follow the instructions provided for the hardware you buy. Mount a piece of trim board to the outside of this notch so that it will be completely hidden from view.

Next, drill the holes for adjustable shelving using the Kreg shelf pin drilling rig, then attach the trim board to the side pieces using miller dowels. (Note: If you are painting the bookcase instead of staining it, you can use screws and fill them before painting.) Also attach matching trim pieces to the top and bottom pieces of the frame in the same fashion.

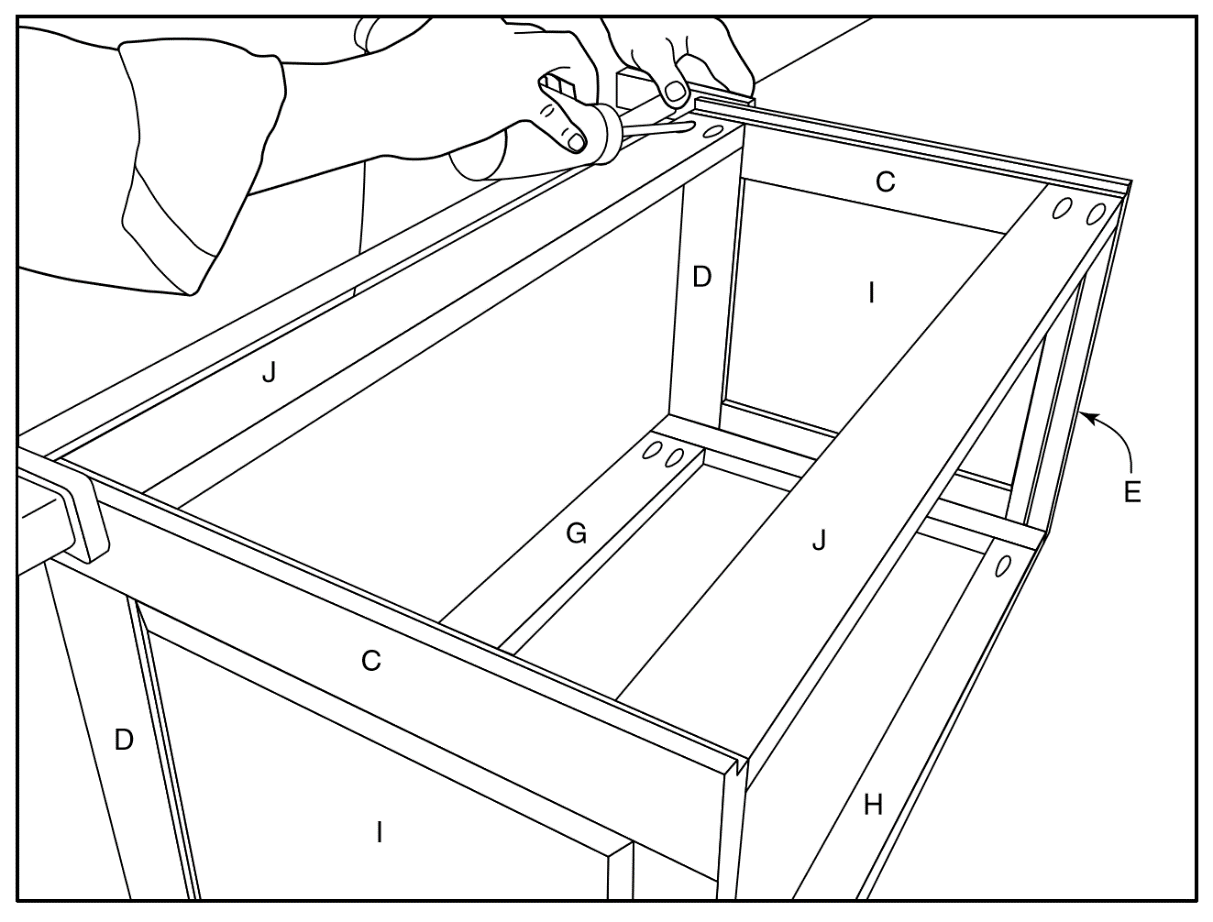

Using pocket hole screws and glue, attach the top and bottom pieces as well as the fixed shelf to the sides. Be absolutely certain to keep everything perfectly square.

Attach the plywood backs using glue and nails or small screws. The bookcases are complete!

Using pocket screws and glue, build the valance. This is just a simple three-sided box made of the pieces you have already cut. There are reinforcing brackets (part of the Murphy hinge kit) that need to be attached to the inside of the valance box, and a roller track that gets mounted to the underside.

The lower roller track is the load-bearing element of this build, so it needs to be based in a piece of hardwood that gets firmly attached to the floor. Cut a dado down the length of hardwood so the roller track fits neatly into it. One and also needs a hole routed into it to accommodate the pivot hinge. See the hardware instructions for all of the details.

Now install the appropriate hardware to the top and bottoms of the shelving units and mount the long hinge on the backside to join the two pieces of your bookcase. With some help (yes, this is quite heavy now) stand the unit up on the base track, and mount the valance firmly to the wall studs at the appropriate height.

Your secret door/bookcase is now installed! The only thing missing is a clandestine lock to keep it from rolling open and exposing your hidden room.

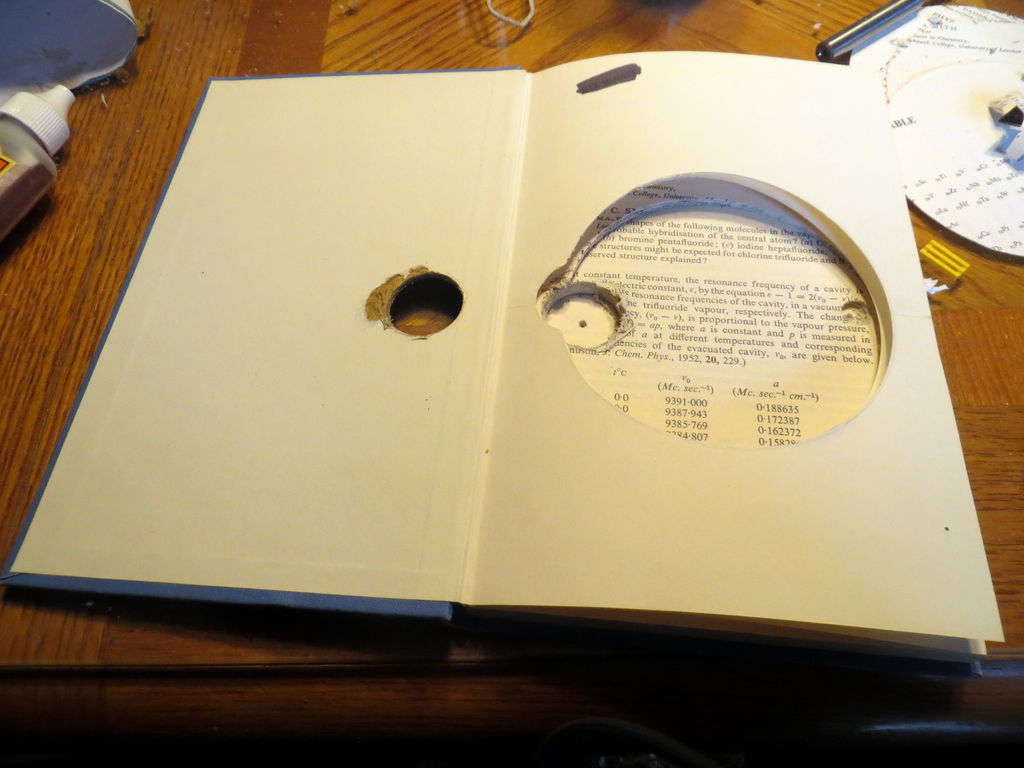

On that center fixed shelf, set a sturdy book that you never plan to read. Open the book so that only the cover remains flush against the inside wall of the shelf, and drill a hole straight through the book and both bookshelves.

Attach a bolt through the bookshelf that won’t have the secret book with a nut on each side of the shelf wall.

Drill the hole on the side with the secret book large enough that the head of the bolt can pass through. Cut a 2-inch or so hole in the book cover and mount a piece of sheet metal to the inside. This sheet metal should have a notch in it that the bolt head will slide into when the book is pushed into the bookcase. Pull the book back and the bolt will “unlock” the secret door.

Cut the edge of the pages back far enough that you can mount a piece of wood between the covers, and screw both covers firmly into place. Attach a dowel rod to this piece of wood and drill a hole in the back of your bookcase in the appropriate spot to allow this dowel to stick through to the secret room. Moving this dowel back and forth allows you to open and lock the door from the inside.

Conclusion

Whether you want to just hide an ugly alcove only used for storage, carve out a private place for yourself, or create a truly hidden “safe room” in your house this bookcase may seem like a cheesy throwback to an old-fashioned movie concept. But it works, every time.

Hope you found this wooden bookcase plan useful, for additional step by step DIY woodworking plans visit JoineryPlans.com.

If your dog has a life anything like mine does, you have to admit that he’s a member of the family. At dinner time, all of the humans sit on nice chairs at a beautiful wood table. But poor little Frankie eats out of a bowl on the floor. It’s time to change that.

My thanks to the folks at Minwax for giving us this tremendous design for a dog feeding station. Now, Frankie gets to eat in style and the rest of the family is envious.

Materials

- (1) – 1”x10”x10’ Select Pine or Red Oak

- (½ Sheet) – Fir plywood

- (6) – Pocket Hole Screws 1 ¼” coarse thread (fine thread if you use oak)

- (8) – Pocket Hole Screws 1” coarse thread (fine thread if you use oak)

- (8) – #8 Flathead wood screws 1 ¼”

- (4) – Table top fasteners

- (2 pair) – Small door hinges

- Finish of your choice

- Wood Glue

Tools

- Clamps

- Square

- Pocket Screw Jig

- Drill with bits

- Dander with various sandpaper grits

- Shaper or Router table with bits

- Biscuit Joiner

- Table, Miter, and Jig saws

Check out our essential tools list for every advanced carpenter.

The Cut

Note that this piece is designed for medium to large dogs. If your fluffball is a little one, downsize accordingly. If the cabinet gets too small, you may have to skip the doors and leave the front open.

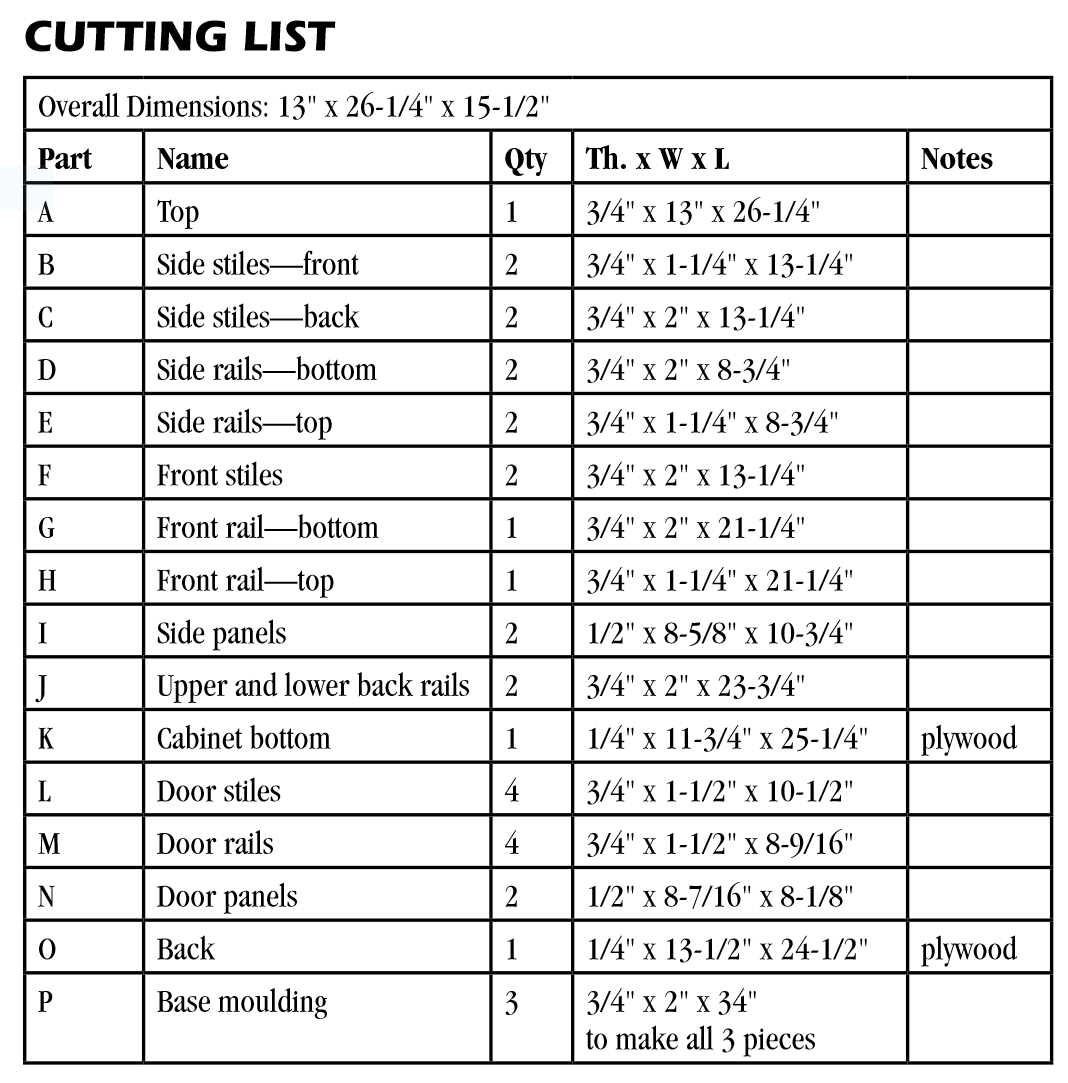

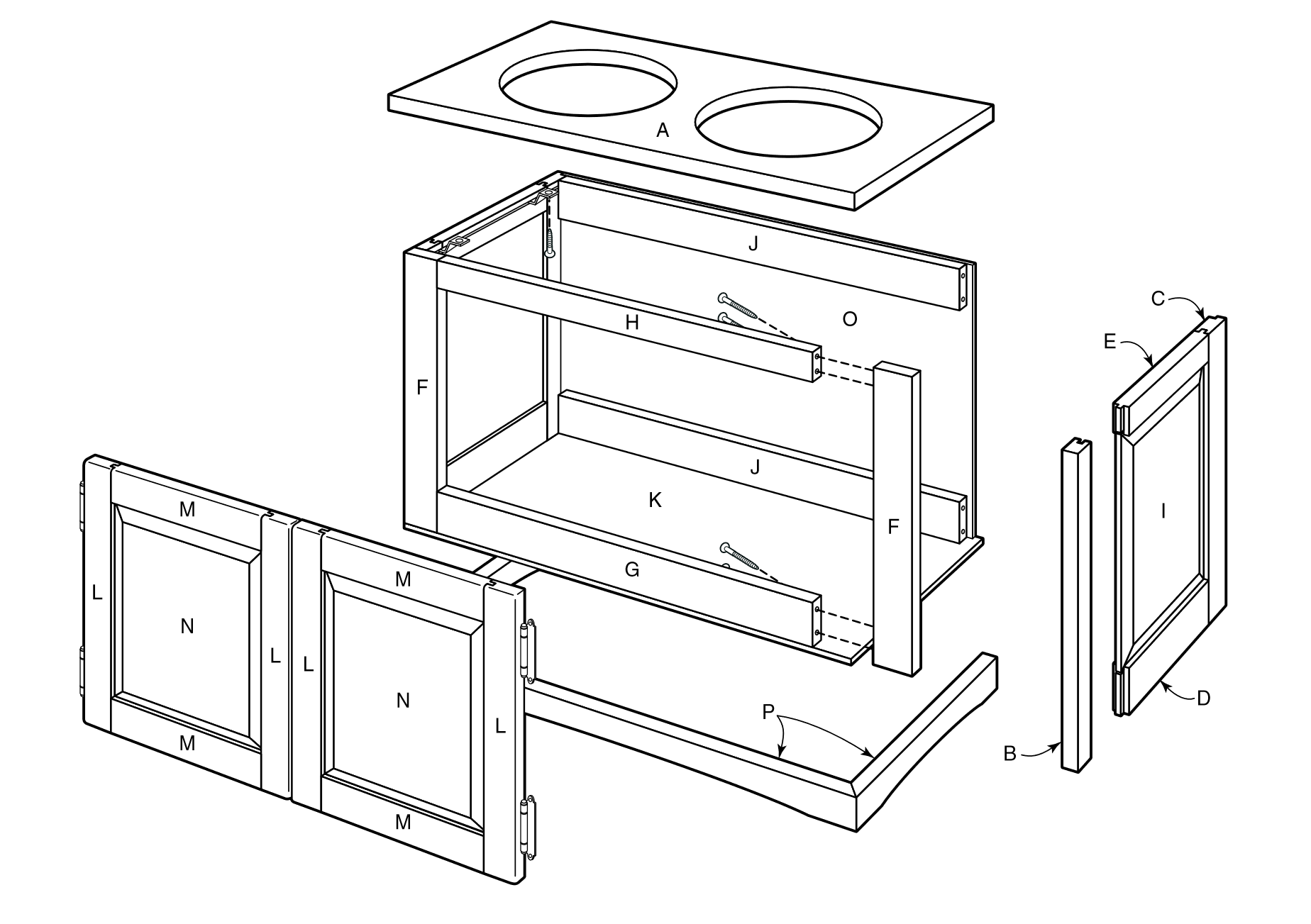

There are 32 pieces to be cut from our single board and half-sheet of plywood. See the cutting list for the details.

The next drawing provides an exploded view of the entire assembly to help make sense of the cutting list.

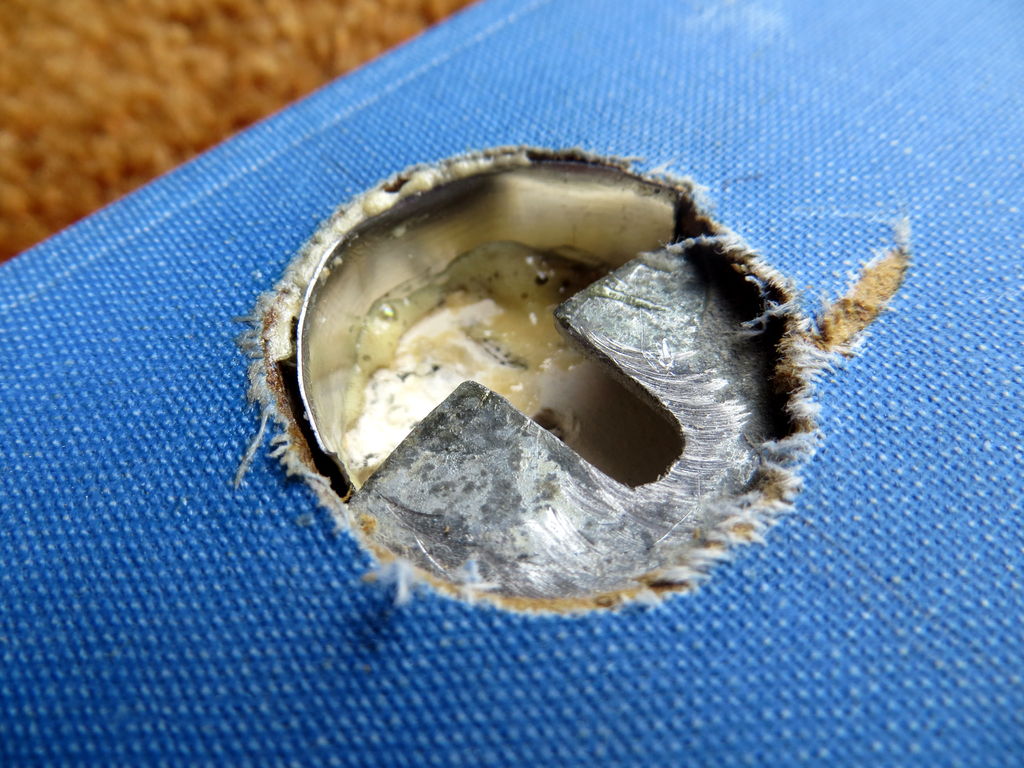

Once you have rough cut all of the pieces, machine them to size. Measure the total diameter of the bowls you are going to use, including the width of the lip (these are 10 inches). Then measure the width of the lip, double that number and subtract it from the overall diameter. That’s how big you should make the holes in the top. Our 10” bowls have a 3/8’ lip. So we double that, which is ¾” and subtract it from the 10” total diameter. That means I had to use a jig saw to cut two 9 ¼” holes in the top.

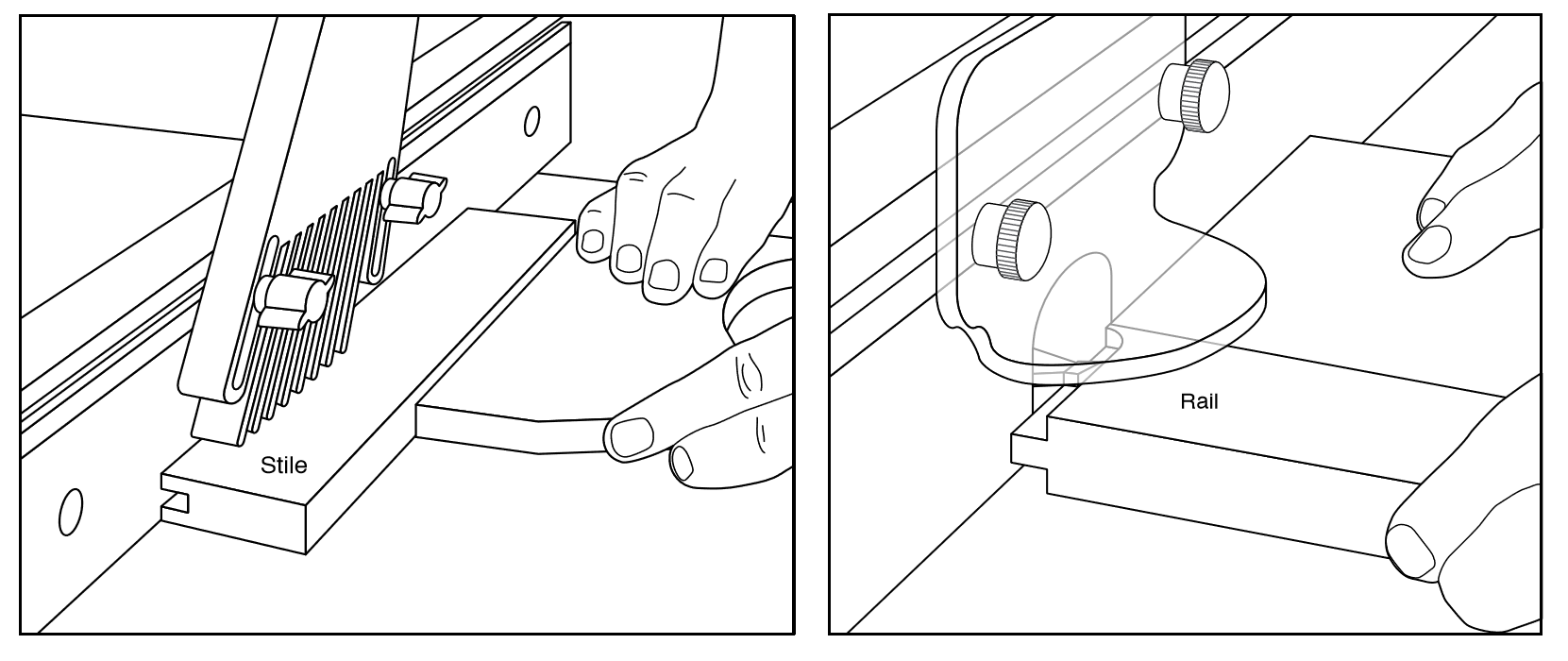

Now create rail and stile joints on frame pieces B, C, D, and E with a tongue-and-groove router bit. Create the groove in all 8 pieces, and the tongue on the grain ends of the 4 rails. With a thickness planer, plane the side panels (I) to ½” thickness, and machine the edges to fit the grooves and create the raised center effect. Note: Allow about 1/8” of space on the rail ends to allow for seasonal expansion of the panels. Then glue the pieces together, making sure they are perfectly square and flat. Remember that you have two sizes of stiles, so glue them together in the proper right and left configurations.

While the ends dry in their clamps, let’s build the frame. Drill 2 pocket holes inside each end of the front rail (G) and one in the top rail (H). Yes, I know the diagram shows 2 pocket hole screws in the top rail. It’s a mistake. (Better to make the mistake on paper than the real piece, right?) Use 1 ¼” pocket hole screws to assemble the front frame.

Now cut two biscuit slots on the front edge of the side frame pieces and the back side of the front stiles. A good measurement is to cut these slots two inches from each end. Also make a rabbet cut on the back edge of the two side frames for the cabinet back (O).

Now dry assemble the sides and front frame and double-check measurements for the upper and lower back rails to make sure your cabinet is perfectly square. Machine the back rails to fit. Glue the side panels to the front, using biscuits for extra strength. Drill pocket holes in the back frame to match what you did on the front and attach them to the sides.

Create the doors in the same fashion as you used to build the sides.

Now, let’s build the base molding. After cutting the molding pieces to the proper lengths, use the router table to apply a ¼” round-over to the top edge. Create perfect miter corners for the base moldings, one corner at a time. A good tip is to leave each piece long on the other end, so that you can re-mit7er a corner if needed. Cut the back end of the molding square with the back of the cabinet once the front corners are perfect.

Draw a curve to the bottom edge of the base moldings using your preferred method. I take a small strip of hardwood and bend it into a bow shape. While I hold it against the molding, I have another person draw the outline on the molding piece. Then, using a band or jig saw (I prefer the band) cut the curve and sand it smooth. Glue and clamp the molding in place and secure it with wood screws from the inside of the front and side framing pieces.

With the router, cut a little cove on the top inside corner of each door, to act as a pull. Alternatively, you could mount door pulls on each door.

Mount the hinges about two inches from the top and bottom of the doors, making sure to pre-drill all of the holes. Allow about 3/32” space between the doors to allow for free movement.

Cut and install the cabinet bottom and back from the ¼” plywood. Lay the top upside down on your bench and the cabinet on top of that. Install the tabletop fasteners according to the requirements for the hardware you have selected.

Sand everything completely and apply the stain or finish of your choice. Do not secure the bowls in the frame because you will want to remove them for cleaning. If you have cut the holes perfectly, they should rest snugly in the holes, yet lift out easily for cleaning.

Conclusion

This is actually a fairly complex build for something as seemingly simple as a stand for a couple of dog bowls. But here’s why I suggest building it. I view this piece as an introduction to cabinetry-making. It calls for extremely precise measurements, detailed woodworking with complex concepts and equipment, and the kind of attention to detail that cabinetry-makers take for granted.

Frankly, if you can build this cabinet for your little Frankie, you can build any cabinet. And if this is your first attempt at cabinetry and you make a few little mistakes along the way, well, I don’t know of anyone more forgiving than the family pooch.